LINKS

Make Your Mama Proud

A Memoir of 1973

Part One • Part Two • Part Three • Part Four • Part Five • Part Six • Part Seven • Part Eight • Notes

In memory of Allen Saperstein and our Detroit friends

In 1972, I met Allen Saperstein in Cobb’s Corner Bar in Detroit. He was bartending. I had just moved downtown to go back to college and finish the BA I had started a few years earlier. That was the beginning of many adventures we had together, including raising two children. In 1973, while I was a student, Allen and I bought a wooden box camera from Art Frazier, an old man who had built the camera and used to peddle photos near the Art Institute. We took it out on the Detroit Cass Corridor streets, then to ethnic festivals, carnivals and fairs in Michigan, and finally traveling down south to Birmingham, Alabama. The story of that journey is at the heart of this memoir.

In the 1990s, I wrote a draft of the story and made a pamphlet with the photos. It was entitled, “Falling In Love With Your Memories.” I gave copies of it to a few people; there is at least one copy in my archive at Yale Bieneke Library. I was never completely satisfied with the story, however, and so every few years I would rewrite it again.

In 2018, I learned that our friend who had traveled with us on the carnival route, Halima Gutman, had died; that’s when I decided to go back and finish the story. My son, Michah Saperstein, convinced me to publish it as a website. I thank him for his encouragement and assistance. I also want to thank Mac Gutman, Sally Young, Tony Iantosca and Esther Hyneman for reading drafts and offering suggestions for revision. Special thanks to Isbat Ullah at Long Island University for his help in designing this website.

Part One

I stood by the passenger side of the car, waiting for Allen to unlock the door. Through a web of hanging vines in the French windows on our Willis Street apartment, I noticed the yellow glare from a bare bulb. “You forgot to turn off the lights,” I said. Then we left behind the lights and drove down Michigan Avenue toward Dearborn. Al was wearing a blue tee shirt that day, airbrushed by his friend Stanley Mouse, some mad guy smashing an ice cream cone into his own face. The windows were down, and we were both smoking cigarettes. His braid was tucked behind him, wisps of shorter hair moving with the wind. No air conditioning back then, but on WDET, a jazz horn solo.

We parked our car in the lot behind Norm’s Wholesale Ice Cream. Al took our ice cream from the freezer, paid Norm $15 for the use of the truck, made an order for a hunk of dry ice, ice cream sandwiches and snow bombs. Then we were on our way to a neighborhood near Livernois and Seven Mile Road. The truck we were driving was an old 1960s pickup painted white with a freezer on the back. The first few days Allen drove because it was a stick shift, and I was a little rusty with shifting. But that day I took a turn, ringing the bell and pulling over for some kids who were waving on the curb. He jumped out and opened the back door of the freezer to get their orders.

At lunchtime we stopped at Hy’s Deli, a place his father used to take him for lunch. He loved telling stories about how he made the rounds in and out of bars and restaurants with his father, filling cigarette machines. Perhaps this childhood experience kindled his interest in street and carnival vending. Up and down the blocks we angled in and out. Occasionally a gang of kids would surround us with ill intent, and we’d speed away around the corner.

Once a week in the afternoon we’d park our truck behind a nursing home on Petoskey Avenue to visit his grandmother. She smiled when she saw me, gave me a big hug. Shiksa, she said with affection. Then she sat Allen down and told him some biblical story about brothers who were feuding, hoping he would soon make peace with his older brother. They had been in conflict over a management-worker issue from a few years earlier when Al was working in the yard of a steel company and his brother in management. Once his grandmother gave me a string of fake pearls and an old dress, hoping I’d stop wearing torn Levi’s and help straighten her grandson out, get him to give up his bad habits, i.e. drugs, and become a business man. Working on an ice cream truck wasn’t quite the business idea she had in mind.

At the end of the day, we would count our money, cook a pot of vegetables to share with our neighbors and then we’d go down the block to Cobb’s Corner Bar to drink and dance with our friends in between the tables to Bobby McDonald banging away on the piano. (End Note #1)

While we were selling ice cream that summer, Al also worked as a bartender at Our Place on 3rd Avenue, across the street from Anderson’s Garden, a bar known as a hub for prostitution. During the school year I worked part-time at Wayne State as a student assistant in the Dean’s office while taking classes for my BA degree, but for the summer I was off. Sometimes I would model for art classes; they liked my boney body. I remember Al sitting in the back of the room watching students draw while I sat naked on a chair on the stage. I remember imagining the students standing naked at their easels.

For a short time, we were supers in our building, but that didn’t last long. We were not all that handy and it was awkward trying to get our friends to pay their rent. Another way we made money was by selling marijuana. I remember guys from the bar coming by our place to pick up nickel bags. The tenor sax for the Hasting Street Quartet, Dedrick Glover was a good friend of Al’s. I made posters when they were performing at Our Place. Dedrick’s older brother Pete was a close friend of Al’s, too. I remember standing at Pete’s apartment door on Selden Street waiting for four locks to crank open. “So, you’re the girl I’ve been hearing about. Al’s my man. Be nice to him,” he said with a deep guttural voice. A woman dressed in a tight red vinyl skirt rang the buzzer and went in the bedroom with Pete for a few minutes. When she left, Al turned to me and said, “Barb, stay here for a few minutes. I’ll be right back.” He kissed me on the cheek. Maybe he was buying drugs. At that time, I didn’t think much about it.

Near the end of the summer, we sat on the mattress on the floor in our bedroom and counted our money. We had enough to buy an old right-hand drive postal car from a city auction and take it on a road trip. First, we went to the Upper Peninsula to see my sister Patti. We had to hitchhike for a week or so while the transmission was being replaced; then we drove across the UP into Canada. I remember driving through a Native American community, the children surrounding us and pointing at the car because it was right-hand drive. We stayed in youth hostels. I remember wondering at the time if Al was too old to be considered a youth, maybe I was too. I was 23 and he was 31.

In Montreal, the hostel was run by a religious organization and the sexes were divided into different sleeping areas. We stretched out on the floor in a lounge area, dosing and snuggling, while waiting to separate for the night. In the morning before we left to head back to Detroit, we drove up a narrow street with a steep incline. In the store window, I saw an antique rose-colored felt hat. I liked it, so Allen jumped out and bought it for me.

Part Two

Al’s friend Lynn Bogorad drove an ice cream truck, too. In fact, she’s the one who originally turned us on to the idea. When the ice cream season was almost over, Lynn came into Our Place. She and Allen had a plan; she would challenge one of the pimps to a pool game, and Al would back her. She was exceptional at playing pool and pinball. I used to retell this story, imagining it was me, but no, I was never great at playing games like these. It was Lynn. I remember her sitting down at the corner of the bar whispering with Al. She was petite and was wearing a levi jacket. She put a quarter on the table and played her first game with Indian Joe. With each shot she sank two or three until she won the game. Then Lamont came in. He was wearing iridescent red pants and a wide-brimmed black hat. The prostitutes he managed were working across the street at Anderson’s Garden. Lynn dropped a quarter in the jukebox and Marvin Gaye blasted, “I bet you wonder how I knew. About your plans to make me blue. With some other guy you knew before . . . ”

Lamont came over to the bar and whispered in my ear: “I told you girl—anytime you want to give up that beatnik, I got a place for you. I’m definitely not jiving you.”

“Oh, sure thing,” I said, pulling my hat down around my eyes.

Then he racked and Lynn broke, sending the cue ball into the rack sideways, with three balls dropping into different pockets.

“Lucky shot, honey.”

Al kept drying glasses and washing down the counter as Lynn walked from one side of the table to the other, sinking balls and occasionally hitting the overhead lamp, its angular light flashing back and forth between them. Lamont stepped back rubbing his hands on his slacks. “Ain’t nothing but luck for a woman to get those balls.”

Al was chewing on a toothpick. Lynn purposely aimed off center, grazing the number six.

“Like I told you, hippie girl, you were just lucky.”

Lamont took aim and knocked two balls into pockets, one after another. Then Lynn kicked the cue ball off the rail and knocked the two ball into the corner pocket. Then she took all the rest. Lamont peeled off a five-dollar bill and looked around the bar at a few women who worked for Chuck and a few other guys—they were all looking at him as he gave her the bill.

He took a deep breath, and then he removed a fifty from the center of his roll, laid it on the table, and challenged her to another game.

Lynn looked at Al. He nodded, then she hit the cue ball, and on the break, she pocketed three balls. After each shot, she brushed her long dark hair out of her eyes.

Lamont chugged down a shot of vodka and then leaned on his stick, looking around. When he took his next shot, the cue ball dropped in a corner pocket. Lynn took the second, third and fourth game. Seventy-five. One hundred dollars. “Shit,” he said.

Then Vanessa came rushing into the bar. She walked over to him: “I’m out here on the street, Lamont, breaking my ass for you and you’re in here giving my money away to some white bitch?”

“Can’t you see, bitch, that I’m busy.” He ordered another drink.

Another night I was sitting with my chin in the cup of my hand, my elbow resting on the bar. I was smoking a cigarette. Al wiped down the counter and told our friend Joe Schlick that he had had enough to drink and should go home.

Joe stood up, put on his black trench coat, and flicked his ponytail outside his collar. “Just remember, Red, I always pay for my drinks,” he said as he stumbled out the door.

Crack—the balls were spinning on the pool table. I stirred my rum and coke with the straw and pulled the brim of my hat down around my face. A woman wearing a tight black skirt, high heels and dramatic make-up sat down next to me.

“You seen Lamont around?” she asked.

“No, I haven’t seen him all night.”

The night before we had given another young woman a ride. Lying on the floor in the back of our car, she was crying and shaking—afraid her pimp would find her. We dropped her off at a house on Commonwealth Street.

Al moved up and down the bar. Then he played a game of pool with Chuck. Chuck took five dollars from Al’s hand and carefully put it in the middle of his roll of bills.

Then Al slid down to my end of the bar. “Watch out for that guy in the corner over there. Maybe you should go in the backroom. I think we’re gonna have trouble.” I moved further away to the end of the bar.

A tall skinny guy put a quarter on the table. Chuck turned around and faced him. “You motherfucker . . . You keep away from my girls!” Chuck smacked the guy on the head with his pool stick, cracking it in two. Suddenly the bar was full of people.

From behind the counter where I was hiding, I heard a woman yelling: “Lamont! Put that gun away! We don’t want that girl!”

“Shut up, bitch!”

Al flashed the lights on and off. His voice sounded over the fight. “Everyone out! The cops are on their way. Everyone out!”

The group pushed and shoved each other as they went out the door. Then Al locked the door, dimmed the lights, and the noise started to move into the distance.

By then, I was huddled in the back room.

Right before closing, the owner showed up with four friends to take the till. Sometimes they stayed all night, partying with the doors locked.

Sometimes the bar was wild like this. Other times it was lazy and cool with jazz or poetry readings, most people then sipping on cokes.

It wasn’t long afterwards when Our Place closed, becoming a soup kitchen, renamed “His Place.” (End Note #2)

We often got together with friends who lived in a communal house on the west side of Detroit, the Collins family. Everyone played some musical instrument. At the time, I was shy about what I didn’t know, so I only listened. Or maybe I turned a shaker. This household grew a lot of their own food, baked and sold bread to supplement their income and sold drugs, like many young people we knew. They were peaceful and creative. One has to remember our thinking about drugs was quite different at the time. In fact, one of the psychology classes I took at Wayne was called “Altered States of Awareness;” we studied zen, meditation, yoga and psychedelic drugs; the graduate student teaching the class helped us buy acid and psilocybin mushrooms.

The Collins family had two young children, and Doreen was pregnant with a third. We arrived at her home in the morning, minutes after her baby was born. The light, smell and sounds in the house were glistening with his arrival. Everyone was whispering. As the morning light streamed into their kitchen, I knew right there and then that when I had a child, she would be born at home. Unfortunately, their communal bliss was soon broken. Marianne, a young woman who lived with them died from a brain aneurysm, and her baby was left motherless. She was in her early twenties. Then the FBI came to their house with machine guns and arrested John for selling drugs. After that, the family moved to Ann Arbor, and I heard that Doreen had opened a bakery.

Part Three

One Sunday, the sky was wide and blue like it is on many summer days in Michigan. Traffic was sparse on Woodward Avenue. Rodin’s Thinker, was thinking in front of the Art Institute as we climbed the steps up to the three arches. Then we passed into the opening gallery with Diego Rivera’s frescoes of auto factory workers, powerful in their muscular frames, pulling and lifting, and the owners and bosses small and in the corner with their notepads. In the Kresge Court café, Allen and I sat reading the New York Times and our friends were there at other tables, also reading the Times. Above billowing parachutes filtered the sunlight. Bill Tyler was passing from table to table selling his poems for a quarter. Later he might come by to visit us, drunk if he had earned enough during the day.

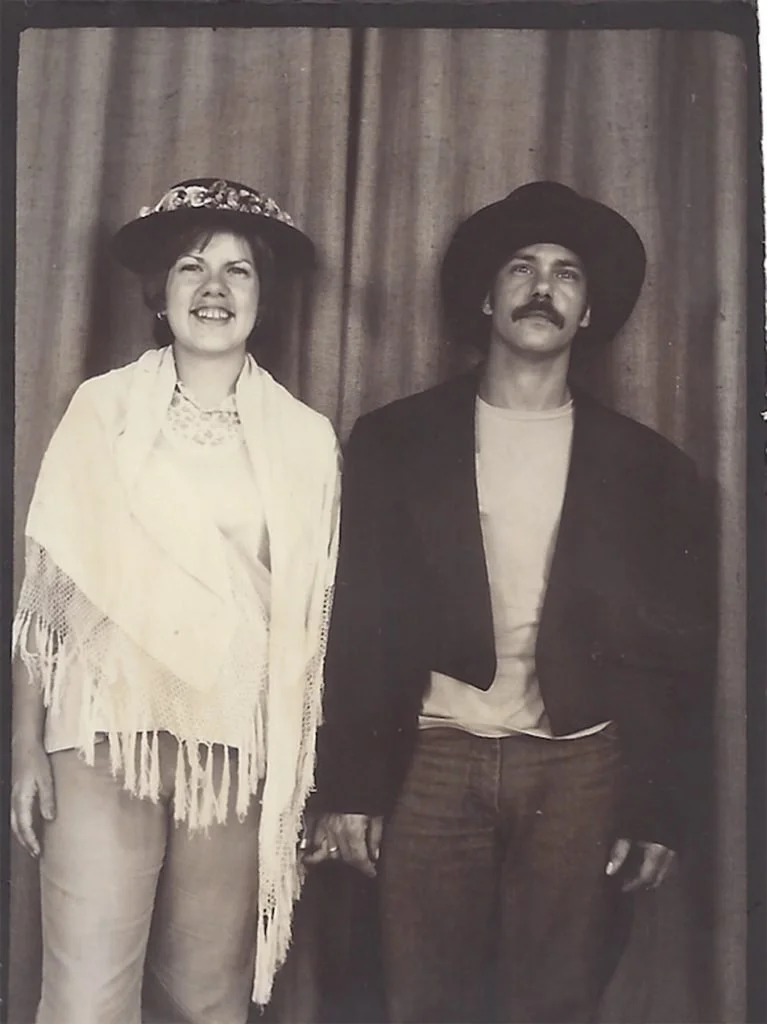

One Sunday in the Spring of 74, we stopped on our way out of the museum to talk with an old man, Art Frazier. Art took photos for 50 cents each. Like a magician he would put his hand inside a black sleeve into an old wooden box camera. We watched as our images were slowly revealed on a white piece of paper in a square plastic cup of water. He took two photos of us, the first visual recordings of our twenty-five-year love and friendship. I was wearing my felt hat, and we were both wearing worn Levi’s. Allen has his arm around me. Back then we wore the same size Levi’s and shared a lot of our clothes, even though he was seven inches taller and twenty pounds heavier.

Art reminded me of the picture man who in the early 1950s used to ride his horse past my grandmother’s house on Alter Road, his homemade camera on the saddle. As a little girl, through the window of my grandmother’s living room, I would watch him as he’d pull his horse over, waiting for the streetcar to pass.

Allen struck up a friendship with Art. He wanted to sell his camera, and Allen wanted to buy it. We had some money left after our trip to Montreal, so Al made a deal with him, and in the Spring of 1974, we went to his room in an old hotel, near Stimson and Myrtle Avenue. The room reeked of bug spray and alcohol. His camera, he explained, was the prototype for the Polaroid. I took notes as he explained to Allen which chemicals to buy, how to mix them and how to use the camera. When we left with the camera and bags of supplies, I never saw Art again, but I’m sure Allen stopped by to see him now and again because he was like that; he liked listening to people tell their stories. He had a very heartfelt way of connecting with others.

In the following spring, we found a flat at 4711 Avery Street with four bedrooms. We had a few roommates, a couple of dogs, lots of books and guitars. The branches on the big elm tree in front of the house were leafless, and many of the houses on the block were abandoned and in various states of disrepair, but our flat was full of activity—cooking, dancing, music-making. My brother moved in with us, then our friend Mike Clarey.

I was going to school every day while Allen still worked in the bars; Bob sometimes took classes, but mostly he played the guitar and wrote songs; Mike worked for an ambulance company and every night he’d tell us stories of despair and emergency. Upstairs, there was another group of young people—Ralph Koziarski and Diane with their little girl, Gary Saner, Tim and some others. I remember the sounds of Ralph first learning how to play his saxophone. On the weekends the ceiling would vibrate from their wild dancing.

On the roof of the house, our landlord and good friend Eric Shreve had built a small apartment for himself. He was about fifteen years older than us, and he’d grown up in the house. He cultivated marijuana plants outside in the summer on the roof and inside in the winter. His classical music drifted downward into our flats.

At first, we experimented with the camera, setting it up on its wooden tripod in the yard of our flat and on the streets in the Cass Corridor. We practiced mixing the chemicals and playing with the settings until we learned how to use it. There were three small stainless-steel tanks under the wooden box. We would reach inside the sleeve into the box, clip the photo in front of the lens, pull the lever to take the photo, then we’d move it into the developer tank, then lift it from there to the tank with the stopper, and then the bleach fix. When the photo was ready, we would take it out of the sleeve and put it in acetic acid and water (or vinegar and water if we didn’t have the chemical). Then at the end, we’d put it into a small plastic container with water and color, either black or brown for a sepia finish. The customers would watch as their images slowly appeared. Even though everyone was familiar with Polaroids, it was still like a magic show.

The photos that still exist are mostly those we took to adjust to the outdoor temperature. How much chemical we would use and the amount of time the photo was submerged depended on the weather and the amount of sunlight. In our first practice session, we stood against the back of the house and tried to follow Art’s directions.

Looking at these photos, I remember how playful Allen was, taking on various personas and always teasing me. In one photo, he’s sticking his hands through my armpits; his white hands glow against the dark background of our house. Then a double exposure of our roommate, Mike pointing out and away at another Mike, one a ghost and the other appearing slightly more alive. The shadow is the light revealed by the chemicals. Mike was always quiet and kind of shy. But then he’d do something radical like jump out of an airplane in a parachute, catch the wind and glide downward. Maybe at the end of the day we’d go into the house and bake bread, everyone taking a turn at kneading and rolling.

In this photo, Eric looks to the side, the light bouncing off his white cutoffs. He was one of the few men I knew back then who was openly gay. Gay men didn’t usually hang around the Cass Corridor, gay women, but not men; they hung out in another neighborhood, I think near Palmer Park. I remember Christmas Eve a few years later in Eric’s apartment, Ave Maria blasting and those big lazy marijuana plants growing in the bedroom. Our six-week-old baby was lying on the end of the couch wrapped up like a papoose.

Once after we moved a few blocks away, I was home alone with two sleeping children, and I heard someone trying to break in downstairs. Allen was out with his friends. This was many years before we had cell phones. I tried calling the Del Rio Bar, but he wasn’t there, so I called Eric. He came over with a rifle circling the house, but the intending intruder was already gone. Detroit had a very high murder rate at the time. One of our friends, Dennis Pruss, had a poetry magazine called Murder City Poetry.

In another photo, I’m wearing a striped tee shirt, hands on my hips, one foot over the other, a skinny body under a big flannel shirt, a pack of cigarettes in my breast pocket. Around about then, I guess we were supporting Phillip Morris. Written on the back, $5.00, apparently the day’s take, not exactly a lucrative photo enterprise, even then. Here I’m wearing Allen’s shirt, worn and intimate. His shadow bent at the crease between the wall and walkway.

Bob named his cat Marfil after rolling papers —I loved holding her big body against my chest. Allen leans against the wall, one foot over the other. A few months before Allen died, he said the reason he never quit using drugs was because he never felt normal without them. The odd thing is for the longest time I didn’t know he was still using. I never noticed anything different about him because he was always able to maintain a calm and clear mood. I suppose this is similar to the way we can’t tell when a person is taking an anti-depressant under a doctor’s prescription. He never had that option.

The light makes a dark spot and then the chemicals reverse it. Allen is leaning not on his left knee, but on his right knee. Everything is its opposite. I see his hand resting on his knee. I knew those hands in reverse very well.

Our neighbor Ernie moves his hands so fast that he leaves behind a white blur. His children and grandchildren lived in the house next door. He must have been a child when his family came to Detroit from Appalachia, maybe in the 30s. I remember riding my bike down Avery Street away from the tree and down to his little beer and pop store on Warren. High on acid, I coasted along under big half dead elm trees. I quit taking psychedelics after a while because Allen had to go into the hospital for open heart surgery because of damage caused by his drug use. I wanted him to live; I didn’t want to encourage him to continue using drugs. Also with psychedelics, I almost always plunged into a never world of darkness and it took weeks to resurface.

When we opened our front door, the dogs would leap into the living room and then back out the door, racing around the neighborhood and that tree where Bill and Ann Kennedy are leaning; In this photo they are still in love with each other. Not too long after they went their own ways. Bill would often egg me on, saying outrageous things about women. “All she needs is a good fuck.” I’d fly into a rage and he’d laugh at me. There was something kind of roguish and charming about him even though he was definitely sexist and would not have done well in the age of “Me, too.” Allen must have recognized some tenderness hidden behind his macho stance because he was always there for Bill.

A cigarette in his mouth and his beard wild and unkemp. My brother tears open his shirt, almost as if he wants to throw his heart on the sidewalk. Of course he was posing; he is actually a gentle caring person, but maybe there is some truth here related to the extent of his suffering after spending a year in Vietnam and being wounded. Every so often, he and his friends would gather on the front porch and blast their electric guitars, sending the dogs far down the street.

All those legs in this photo belong to our upstairs neighbors, Diane and Gary. When they held parties, everyone would dance so hard that the entire wood frame of our house would shake and tremble from their stomping feet.

Dennis looks young and easy-going. I remember him apologizing, endlessly apologizing. It was easy then to just think, oh, that’s Dennis, so guilty and too young to be so apologetic. We were young, too. His white shoes on the avenue, feet open at an angle. Drinking too much was ok, too. We knew nothing about his childhood, and we didn’t ask.

Joe Hendricks crouches down beside his bicycle. Once Joe and I rescued our motorcycles from a city warehouse where Allen and I had been storing them. A friend called saying the garage doors were wide open and they could see our cycles. Someone might steal them. Allen was out of town, so I called Joe to come with me. As we were walking the bikes west on Forest Avenue in the dark, the Detroit police stopped us. They refused to look at the titles I had in my pocket. Instead, they handcuffed both of us and put us in the backseat of a police car. Because Joe was black—we were sure of that—he was locked in a cell in the basement while I was handcuffed to a chair in the station. The police laughed at me. Then they made some phone calls and discovered that the motorcycles were indeed mine. So, they delivered both of us and the motorcycles, now with new dents, back to our flat. Here Joe kneels down in this photo and poses in front of his bicycle. Bob tells me on the telephone that he ran into Joe some years ago and he had become an evangelical Christian.

I don’t remember this guy’s name, but I remember his anger and that his father was a political figure, maybe a judge. He was using drugs one night and he fell asleep with one leg over the other. From then on, he walked with a cane. Blurry me with my head moving faster than the camera. I smoked three packs a day. My father worked for Chrysler. Loop. The loop of my shoulders and arms. The light actually makes a dark spot on the paper and then the chemicals reverse it. So Allen is not really facing that direction with that dreamy look.

David Snow pats his belly while he leans against the sandy bricks of the Bronx Bar beside his friend Keith. The top of David’s head cut off, perhaps when Allen tried to fit his tall body into the frame. Or maybe I took this photo. David’s smiling in a timid way, kind of hinting at the child he once was, and not with the cynicism he sometimes expressed. He and Al were like brothers. Years later he moved to Portland Maine where he continued to make his art and where he worked as a drug counselor. After Allen died, he came to visit me in NYC; he gave me an autobiography of his grandfather, Wilbert Snow, a poet laureate of Maine and the thesis advisor for Charles Olson’s MA on Melville. He recalled Sundays at his grandfather’s house when Olson was there. All the links that tie us together before and ever after. Wilbert’s autobiography, Codline’s Child, now sits on the shelves of the Poet’s House with David’s inscription to me.

Written on the back of the photo of David and Keith is: “Cowboys & Outlaws.” Some years back David wrote and asked for this photo back. I sent it to him, thinking I had scanned it. In 2008 he died, living longer than most of Allen’s friends. I couldn’t find the photo, and it was important to me that David be part of this story. Then in May 2018, I found an email address online for one of David’s brothers, Jacob; I wrote him and he wrote back immediately with a scan of the photo, lots of scratches; apparently carried in David’s wallet, reminding him of his earlier life and friendship.

Part Four

On Sunday mornings, a group of friends would often gather at our flat for brunch. Allen loved to entertain. One Sunday, Billy Reid, table tennis star and historian of the lineage of the hip, brought a friend with him, Halima Akhtar, aka Halima Bunnell. We were looking at some of the photos from our camera adventures on the streets when Halima started telling us how she had been working in the ethnic festivals on the waterfront, selling astrology charts and reading palms. She had done very well and was thinking about working some county fairs. She talked about how much money we could make with this camera by taking it to the ethnic festivals and county fairs. Allen listened intently. Years earlier, he had worked with circuses and what she was saying interested him. “You could dress them up in antique clothing. You’d have lines of people with this camera.” They were both drinking vodka and talking excitedly.

Born in India, Halima’s father owned a perfume factory in downtown Detroit; her mother was born in the hills of West Virginia. These two ethnicities combined to create her unusual beauty. She sometimes looked as if she could be Native American, maybe Apache. Her parents were already separated by the time we met, and she was living in a flat on the Eastside of Detroit with her father and her teenage daughter. Halima had divorced several years before we met. I search for her husband, the artist Dick Bunnell, online and find an article in the Detroit Free Press in 1959 with the headline: “Beatniks? Not Us, They Say.” They must have been married then.

“You can make a fortune so fast,” Halima said, looking at the photos. “They really look like tintypes.” She had long dark hair and talked animatedly with a robust laugh. By the look on Allen’s face, I could see that he was getting hyped up about this possible adventure.

“We could set up a tour and do it together,” he said.

“In the country fairs, we will make so much money,” Halima repeated, “especially with your camera.”

What we didn’t realize at the time was that she had a habit of telling you emphatically what you wanted to believe.

We reserved our spot at the Michigan State Fair about five spaces away from where Halima would set up her booth. Then we had to figure out how to build a booth. Brad Decker, a young man who was living with the Collins family, had some carpentry skills. He came by and helped us build it out of plywood and 2 by 4s. It was literally an 8 x 8 x 8 wooden box that we could take apart and reassemble. We painted it bright red. Later we learned that we should have slanted the roof. The top protected us only from sunlight, not from rain. Allen put in the electricity. I think Eric must have come downstairs and put his two cents in.

Our friend David Snow painted the sign: “Make Your Mama Proud.” I don’t remember how we came up with the name for it, but there probably was a group discussion. The drummer, Bob Meek, made a bebop mix tape that we played over a speaker hooked on the front of the booth. In this technological age when everyone is photographing everything, it seems odd, but we never photographed the booth or the sign. Even the tape has disappeared, as well as parts of the camera.

We scoured the secondhand stores and put together a box of clothes and props so we could dress people up, as a farmer and his wife with a pitchfork, Bonnie and Clyde with machine guns, the roaring twenties with a tuxedo and top hat. We had lots of weird purses and hats. At the Michigan State Fair in August of 74, Detroiters loved the camera and the idea. We did very well. We sold lots of photos. I remember friends and family coming by. They took their best shots home with them; we kept the test photos. That’s why so many of ours are dark and blurry.

Allen with a full beard and long ponytail. The year after we returned from our trip his beard and hair got shorter and shorter as he prepared to become a father. In one photo, he’s wearing a tux over a tee shirt and Levi’s and he stares straight into the lens. The light is on his left thumbnail, no right, and on the hankie hanging from his right pocket.

Suspenders and a money apron, big floppy hat, ponytail over my right shoulder. I was ready to swoon from the heat at the State Fair. I remember going to the first aid office for salt tablets.

Our friend Billy Reid was a table tennis wizard who traveled to China in the early 70s, part of an effort to open up relations between China and US at the time. He also followed a macrobiotic diet and knew everybody who knew anybody who was anybody in the sixties. And he kept charts of all their relationships. In this photo he’s wearing plaid pants and a crisp white shirt while eating an ice cream cone. Once while he was staying with us, and while Allen was sleeping, he tried to talk me into lying down with him. When I shook my head, no, he accidentally spilled candle wax on my favorite Joni Mitchell album, Blue. “I am on a lonely road, and I am traveling, traveling, traveling, traveling, looking for something, what can it be?” It wasn’t that unusual; at the time we were somewhat freer about sharing our sexuality.

My sister Patti’s long hair is pulled over one shoulder, a flowery hat on top of her head, her hand holding the shawl closed. She was home from college for the summer and working with us. That was the year college students were making the news for streaking naked through various locations. When Patti returned to college, she did her thing, running across a football field in Marquette, Michigan. In another photo she’s wearing an apron, squinting into the power lights, her hands moving in a blur.

Holding her purse, my stepmother Jean’s stands under a big fruity hat. I think she is also holding the end of my father’s machine gun. Even in a tuxedo, my sister Ginny’s husband stands still and straight forward like a farmer with his pregnant wife.

Under a top hat, little Teddy Isola stands beside his mother. When I first met Teddy and Judy, they were living on Seward Street. The apartment was dark and dismal. Whenever possible, we’d take him along with us on our ice cream truck to give him time away from that life. He carried a little notebook where he drew cartoons. This photo documents a calm moment in their lives. Judy and her new husband Bob Meek were both off drugs. They had just moved into a house in Grosse Pointe and were trying to live a straight life and help Teddy grow up. A few years later, Bob od’d in a hotel downtown and died. Shortly thereafter, Judy went on a kidney machine; she didn’t start using again, but she didn’t live for long. Teddy in his late teenage life was a drummer in a punk rock band, taking after his father Frank, a great Detroit jazz drummer. One winter, he caught a deadly virus and died. The light shines off Judy’s cheekbones and that white tee shirt Teddy’s wearing.

Who is this older man? Someone Allen befriended in Detroit, with all his comings and goings here and there. I don’t know him. I never knew him, but he was around.

Part Five

If we were to make money everywhere like we did at the state fair, we thought, we wouldn’t have a problem paying for motels while working in the county fairs. On Labor Day when the state fair closed, we packed up our trailer with all our planks, boards and boxes. We led the caravan in our rusty old Ford galaxy and trailer and Halima followed in her little rusty Karmann Ghia.

In Allegan, we paid for a motel room for a few nights, but we quickly learned that we were not going to do that great there. We sold some photos, but not enough. The people were not as excited as Detroiters about dressing up in front of an old camera. Allen went to a sporting goods store and bought a three-person tent and three cheap sleeping bags. We put the tent up in a nearby campground, and that’s how we slept for most of our trip.

Just before we arrived in Allegan, Michigan, the weather turned cold. Everyone was wearing winter jackets. We had a lot of trouble finding the right settings on the camera. Finally, we started heating the chemicals with a light bulb. I found a big horsehair coat for sale in another booth and added that to our costumes. Maybe country people would like the coat and the pitchfork better than the gangster look that had appealed to Detroiters.

Allen with a bubble gum nose, wearing a tee shirt and a top hat. There’s a white spot from the light on the bubble. Silly, Allen.

On the last day when we finished packing and were driving off the lot, we saw a little white puppy nosing around in some garbage. Someone had left her behind. We picked her up, named her Highway and took her along with us. She stayed with us until we returned to Detroit. When she was fully grown, she leaped over the fence and was hit by a truck and placed on the side of the road. We buried her in my brother’s yard.

Halima said she knew for a fact that we would do much better in Hillsdale. We could stay in her cousin’s house, and there was more money in the village. We should do very well, she said.

Hillsdale was rolling country with many big horse farms. When we arrived, Halima contacted her cousin. He was working for the city. We stayed there one night. I remember walking through his gleaming modern kitchen. To him, I’m sure we looked like the scruff of the street, especially with our puppy. After one night in his house, we set up our tent in a field behind the cow barn and the pasture. We showered somewhere near the animals in the cow barn. For me, the experience was growing more and more frustrating. I started to hate having my photo taken every morning, afternoon and evening.

The Hillsdale Daily News carried a news clip about us on September 23, 1974. Sometimes Allen liked to use my last name. I’m not sure why. Perhaps he thought we’d do better here in Christian country without his Jewish last name, Saperstein.

Many of the customers in Hillsdale were upset about the horsehair coat. One woman called us horse murderers. I have to admit I wouldn’t buy a coat like that now; I’m hoping it was made from a horse that died a natural death.

One afternoon I went down the road to order a hot dog in a concession trailer. A fat red-faced man asked me, “Whaddya want girlie?”

“One hot dog with mustard,” I said smiling.

Then he suddenly reached over the counter and caught my nose between two of his fingers and twisted it. I screamed and he laughed. I ran back to the booth, crying. I remember Allen furiously charging back there. I don’t know what he said, but I didn’t go near that concession again. Many times in my young life, I was belittled, pinched or even chased because I was young and female, vulnerable, an easy target. Several times Allen would come to my defense even years later when we were separated.

Some of the carnival people would stop by our booth to talk with Allen. I remember one guy in particular with a blackened face. He worked in the back of the horror ride (called the dark ride) scaring people. He also hung around Halima’s booth because she would give him lucky numbers and talk to him about his life and work. A young mother, Cheryl used to hang around our booth. She had run away from her husband and was worried that he might show up. She was working as a ticket taker on the rides. At night she slept in a car with a few other carnies.

Allen looks troubled in this photo. I think we were bickering. There was very little money, and we were grubby from sleeping in a tent. One day we were so irritated that we stuck the hat rack in front of the camera.

We didn’t do well enough to stay in motels, but we did cover our cost, food and the gas we needed to get to our next stop.

It was always exciting to set up on the first day and pump our bebop music onto the street. In Bluffton, Indiana, the disappointment came after we were dressed in our costumes, the camera set, lights on, sign out front. To our surprise the customers streamed right past our booth without even looking, and there was no place close by to put up a tent. The fair was set up on Main Street in the middle of town. So, we stayed in our booths at night, sleeping on the ground in our sleeping bags. It was incredibly uncomfortable because the ground was a cement street. And then it started raining. Allen kept propping things up on top of the booth under the tarp, trying to make an angle so the rain would run off of the roof rather than into the cracks. After two nights, Halima had money wired to us so we could rent a room in an old woman’s house for the last few nights.

The daily routine at the Bluffton City Street Fair was as follows: In the morning, the fair closed down for a parade, either the Shriner’s, school bands or the VFW. When the parade started, everyone quit buying and after the parade, there was another parade, then it would rain, and everyone would go home.

One night I was sitting inside our booth in the rain watching Halima standing inside a phone booth across the way, talking first to her daughter and then to a man she was seeing in New York City. Every night throughout our trip, she would find a phone. I rarely called home since I was there with Allen.

One afternoon when I was sitting with Halima in her booth and we had no customers, she started showing me how to use her books to make an astrology chart. She confided in me, “Like your mother and me, you are a Scorpio. Be careful of the drama. Don’t make decisions too quickly.” Then she looked at me and smiled, “When Kirsten graduates, I’ll move to New York to be with Mac, but not until then.”

Halima’s booth was next to some gypsies who called the police and complained that she was telling fortunes (which was exactly what they were doing). Fortune telling and selling must have been illegal in Indiana at the time. Still, it was slightly more popular than our photos. I remember drinking a coke at the bar while Allen was chatting with a policeman who earlier had stopped at Halima’s booth to question her. This sounds like a strange and unlikely activity for Allen, but he was a talker, and he was trying to help Halima. He convinced the police that the gypsies were at fault and jealous because Halima was attracting some of their customers.

What I remember from Bluffton most was the cold cement and the streets with beautiful old houses. Most of our experience, however, was limited to our little box.

Allen seems so serious in this photo, his hands in his pockets, hands on suspenders, hands in surprise, hands on a gun, Allen with a look of concern. And then there I am with my twisted, angry face. I want to go home.

Some guy’s name and address is written on the back of one photo with a note, future plans for the camera. I guess we could have gone to Lexington, Kentucky. But we didn’t.

Part Six

After the fair closed in Bluffton, we started a 600 mile journey down south. For two nights we slept in our cars in parking lots beside roadside restaurants. The trailer was packed with all our things in a very slapdash way with a canvas on top. Allen had refused to let us cut the new rope he had just purchased because he thought it was wasteful. He wanted to keep it intact. It was such a nice yellow rope. Some quirk in Allen’s personality. In Hillsdale, Halima and I ran it all the way across the field, weaving it in and out of the trailer, just to keep it intact. That was ok on the short ride to Bluffton, but as we drove on the highway to Birmingham, the rope kept stretching, and things started flying out of the trailer. The drawer to our little table was full of sample photographs. They flew out on the interstate and then the table went, too. No one was hurt, but we had to stop and retie the trailer several times. Maybe that’s why we don’t have many photos from Allegan, Hillsdale and Bluffton and no photos of Halima during those fairs. They must have gone with the wind.

At the Alabama State Fair in Birmingham, we were stationed inside a building. Halima’s stand was right next to a Bible stand and the men there kept trying to win back her soul, which had apparently been lost because she was reading palms and making astrology charts. We had to move her stand to the other end of the building away from them.

Eight days in Birmingham. Photos of Allen are more numerous because I didn’t want to be photographed. I was tired of sleeping in a tent and wondering if we’d have enough money to eat each day. Southerners walked by, uninterested in paying for a photo of themselves. Maybe only Detroiters liked dressing up and posing. Or maybe the problem was that we didn’t have the same flash as the concessions on the outside aisles with all the lights and noise.

Here Allen is probably upset because we’re not making money. And we must have been bickering. One eye is in a shadow from the bill of his hat. The other is in the light. Looking at the photo, I am a little worried that I might have done something to cause his lips to meet in just that way.

Here I am with a mouth full of braces and braids now opened into two long pigtails. My arms crossed.

This one in the top hat holding his lapels is not the Allen I know, but a character he has assumed. And here he’s holding his suspenders, posing again, silly and true blue, shirt unbuttoned, a watch chain.

Allen in a cowboy hat wearing an automobile tee shirt screened by his friend Mouse of California but designed when he was in Detroit. Now a side view in a top hat. A Sherlock Holmes movie. That tee shirt is so white and there’s a circle of white around his right eye. Mirror images. As if he is pressed against the paper. Allen with haphazard buttons on his jacket.

I am wearing a black velvet hat and Allen’s old sweater, scowl, scowl, scowl. Tight braids, scrunched up face, old tight pants and an ashtray in my right hand.

We took turns leaving the booth and wandering the carnival lot. Once I stopped at a trailer with a voice over a speaker: “Come and see the tiniest woman in the world. Could fit inside a high heel shoe.” Bored, I paid my 75 cents expecting some kind of a show, but instead I found myself standing in front of an open window looking at a little woman working in her kitchen.

When she saw me, she came forward. “Hello,” she smiled. “This is my refrigerator, made especially for me and this is my little table.”

Then a tall teenage boy walked in the back door, leaned down and opened the refrigerator. “This is my son. He is full-size.” He looked at me and scowled.

I dashed out of there, embarrassed for having paid to gawk at someone.

We had certainly spent more than enough time gawking at ourselves.

Our friend Joe Schlick arrived in Birmingham driving a rental car. Once he and I had read the Denial of Death out loud to each other. More than once I had kicked him out of our flat because he had arrived there destructively drunk, falling over and breaking furniture. When he got out of the car in Birmingham, he was so drunk that I took his keys from him and put them into the back pocket of my jeans. When I went to the bathroom, unfortunately, or perhaps fortunately (and accidentally), the keys were flushed down the toilet.

Then he began to drink more and more. In the morning, Allen and I pulled him from underneath a trailer where we found him sleeping.

Everyone thought Joe and Al were brothers. Together in this photo they could be criminal outlaws. Slap happy, Halima and I make monster faces. Then serious Halima with her hands on her hips wearing a beautiful mirrored Indian print. The light is loud on the right side of her face. Her deep voice, big hands, exotic presence.

I remember when we were traveling from fair to fair, Halima and Al would drink vodka together (I didn’t like to drink) and carry on laughing and telling stories. They were closer in age, 8 or 9 years older than me, and they always loved each other like best friends. Halima acted motherly toward me, and oddly enough her birthdate was the same as my mother’s: November 4th, my mother in 1921, Halima in 1939.

The night before we left Birmingham, the carnies had a jamboree under the big tent with strippers and gambling. Even though Al and I were close to broke, and we needed the little we had for a camping trip we had planned to take in the foothills, he joined Halima and Joe eagerly buying lottery tickets and drinks. I watched the woman on the stage peel off her glittery white suit, one piece at a time. At night I peeled off my Levi’s, combed my hair into a ponytail and crawled into a sleeping bag, listening to the sounds of Allen and Halima sleeping. Joe slept in our car.

Part Seven

The next day Halima drove Joe home. Somehow, she got him back into the car after every bar stop from Birmingham to Detroit. He had enough money to pay their way. A few years later Joe drank a couple of fifths, and one night in 1978, he drank enough to kill himself. Here Al and Joe are side by side with their hands at their sides. That worried look on Joe’s face. The youngest of thirteen, his mother, he once told me while rolling with laughter, used to tie him up to a pole in the backyard. It didn’t seem funny to me, but maybe that’s how he dealt with it. Perhaps the worst thing that ever happened to him was winning a workman’s comp case against the state of Michigan; they gave him such a big caseload as a social worker that he had a breakdown. He then had enough money to rent a car, drive out to find us and later drink himself to death.

When the fair closed, we had a little cash. Joe probably gave Al some money, and maybe Allen won some at the jamboree. Now it seems as if we were a bit crazy to travel with no money. What if our old car had broken down? Still, we didn’t go straight back. Instead, we decided we wanted to explore the foothills of the Appalachian mountains. In Birmingham, one of our customers had told Allen about a flea market in Gadsden where we could set up our camera. We stopped there for a few days. There weren’t very many customers, but we made a few dollars to help with the gas and groceries. People kept looking at us as if we were aliens. I guess we were. A young couple with three children stopped to talk and have their photo taken. Then they invited us to camp at their place in the mountains.

No running water, a bunch of kids, a lot of fog, an outhouse. We set up our tent on the side of the mountain and ate dinner with them. At night it was shivering cold in our cheap light-weight sleeping bags. I remember crawling out of the tent to use the outhouse, standing there in the fog looking down into the forest on the side of the mountain.

In the morning as we were heading out, a piece of our tarp came loose and a little box of supplies flew out on the side of the road. Minutes later while Allen was retying the tarp, a police car pulled behind us, the county Sheriff. It was just a few years past the “Easy Rider” film and the civil rights battles. We were tense. “Oh, shit,” Allen said as the sheriff walked toward the side of our car.

“Crazy driving, son. Get out of the car . . . Where you coming from?”

“Taking photos in a flea market in Gadsden, sir.”

A Mustang came around the bend, speeding at first, but then quickly slowed down.

Allen stuck his head in the car. “Barb, find the papers from the flea market and the fair.”

His partner stepped out of the car and waved to the sheriff, holding his hands open to indicate that they had no warrants or outstanding tickets for us.

I could hear the guy questioning Al. “What’s back there in the trailer, son?”

“Equipment for our booth and for taking pictures at the state fair in Birmingham.”

“That fair was over last weekend. What are you doing here?” he said as he reached over to look under the tarp.

“The flea market… now we’re heading for the state camp grounds for a few days.”

He walked toward the back of the car, first looking back at me and then into the trailer. He lifted the edge of the tarp to look one more time. Their blue light was going round and round.

When he was done looking under every corner, we slowly pulled the car back onto the road. Allen said, “Let’s take the Interstate for a while.” We liked travelling on back roads, but this experience shook us a bit.

The rest of these photos were taken when we set up the camera at our campsite. Such a relief to escape from the carnivals. One day we spent the entire day sitting in the car with rain beating down on the windshield. We didn’t have enough money to go anywhere. Then when it was late enough, we crawled into the tent and fell asleep listening to the rain hitting the tent.

On our way north, we stopped at another flea market. We took photos of people against a quilt we had brought from home. Allen’s face is just as he was when I first met him, bartending at Cobb’s Corner. He was wearing a blue skullcap, probably the same cap. When I ordered a little beer, he laughed, gave it to me, came home with me and stayed for nine years.

Part Eight

It was mid-November when we approached the Detroit area, passing by Zug Island, a dark and ominous industrial island in the Detroit River. I looked out the window and imagined the entire economic system of the country extending from the carnival exchange: tricking, buying, selling, some winning, but for most of us, the forever scrounging around for a little change.

In January Allen started bartending again, and I went back to school, working as a student assistant in the Geography Department. We didn’t take the camera out again until July for an ethnic festival on the waterfront. I remember ushering men into the booth with their guns. The dentist had taken off my braces. I quit smoking and started putting on weight. In this photo, I’m wearing an Indian print sundress that’s stretched around my pregnant belly. A baby is pushing against the fabric. Even my hair seems to have gotten thicker. Amazing the way a young body can recover from all those cigarettes.

Allen’s wearing a tee shirt with a monkey in a circle and smile in reverse. We probably picked up Teddy from his mother’s apartment on Seward Street; he often stayed with us for the day. And Mike may have been helping or just hanging around the booth.

Halima’s standing in front of a tree by Cobo Hall, her hair loose on her shoulders. Her customers on the Detroit waterfront wanted numbers and their futures charted. During the ethnic festivals, when she needed a break, I’d sit in her booth and start the charts while trying to talk newcomers into waiting for her to have their palms read. Those who came week after week needed no convincing. They wanted only Halima’s guidance.

The following year Allen bought a popcorn-peanut cart from Danny O’Neil; Danny’s Greek father-in-law owned the concession carts that were set up in downtown Detroit outside Hudson’s and Crowley’s. When Wayne State was in session, Allen would set up his cart outside of State Hall where I was taking classes. On the weekends, he’d set up down at the waterfront with Joe Schlick selling balloons.

I remember a professor at school saying to me, “Well I guess now that you’re going to have a child, your traveling life will have to change.” I looked at her and said, “Why? Of course we’ll go on as usual.” Our daughter was born at home in November 1975. Allen became progressively more and more involved in vending in circuses, carnivals, festivals and on the street while I was studying literature and writing poetry. I still helped out, making caramel apples in our kitchen, traveling once to a circus with him and our baby girl, and once later we took our two little children, a trailer, a friend and another eleven year old with us on a month journey down south to Miami and then to the Florida Keys, selling lemonade and this and that carnival trinket at the sunset on the coast in Key West. That’s another story.

We were happy living together for several years, but then wanderlust of body and mind took hold, and out the door we went in 1983, single with children, migrating together and apart to New York City where I then worked as a teacher and Allen opened Copy Cat, a stationary xerox shop in Brooklyn on 7th Avenue. His store became a neighborhood gathering place with great jazz music playing from 9 am to 6 pm.

When he became too sick to work in 1996, I cleaned out his store and found the camera and some notes, but I never found the wooden tripod or the little stainless-steel tanks for developing film. The darkroom inside the sleeve is now just a dusty little wooden box sitting on a bookshelf in our son’s apartment.

When a life is over, it’s over. When I close my eyes, I can imagine Allen glancing at me from the driver’s seat and Halima looking up from her pillow in the back of our van the day before we dropped her off in New York City. I was holding a baby in my lap, and she was about to start another adventure with her life partner and husband, Mac Gutman. But maybe I’m remembering the photos after looking at them so many times over the years rather than that particular moment in time. That’s the mystery and the trickery of photography.

Notes

1) Bobby McDonald’s photo from the Cass Corridor Tribes website on 11 July 2018.

2) I couldn’t find any photos online of “Our Place” or “His Place” but I located this photo taken a few years later and published in The Free Press of the Chief of Police busting Anderson’s Gardens for prostitution. “Our Place” was a squat small nondescript building across the street. “Chief Hart Leads Raid On Hooker Bar.” September 10, 1977. Detroit Free Press.

3) This photo of Halima was online with her obituary. It reminded me of how she looked when we first met her.

4) Joe Schlick selling balloons with Allen. Photo taken by our friend Harriette Hartigan. I scanned this from a proof sheet.

Page 34: A young man came by the popcorn cart one day and handed Allen an envelope with this photo.

Page 34. Allen Lee Saperstein was born on August 21, 1940; he died on April 25, 1997. Halima Akhtar Bunnell Gutman was born on November 4, 1939; she died on June 1, 2017.